It is my belief that it is of the utmost importance to use every part of any animal you harvest to the best of your ability. When you are raising an animal, there are a lot of resources that go into raising a single pound of meat. Often, especially with ducks, I hear people say something like “It’s just not worth my time to pluck them” or “There’s not enough meat on the wings to make it worthwhile to cook them.” Consequently, it is very common for people to just skin a duck, keep the boneless, skinless breast meat and skinless legs, and discard everything else.

If you’re throwing away the skin, you’re losing all the fat off of a duck. In addition to missing out on a culinary treasure, that also means that right off the bat, you’re throwing away almost 25% of the edible weight of a duck. When you consider all of the water that went into growing the grains and feed that you provide the duck, the feed itself, and all of your time and effort, you start to realize that such a large amount of waste is unbearable. Even if you can personally afford to throw away resources, at some point you have to wonder how much waste the world can afford. I believe that we should all do out part to use our resources in a manner that is either inconsequential or beneficial to the planet.

Every time I process ducks, I seem to change my mind about what my favorite part of the duck is. The breasts are normally seen as the most premium part of the duck, but in reality, they’re the most uninteresting part of the duck. They’re easy to work with and they taste good, but it’s an instant gratification. Some of the parts you have to work hard for can be made into far more enjoyable delights than the breasts. Potatoes roasted in the fat you rendered from the duck; pate made from the livers; hearts sauteed in the fat and served on pasta; a creamy, rich risotto made with a gelatinous stock; crispy stir fried tongues… those are the parts of the duck that are the real treats that you won’t find without doing it yourself.

Because I want to utilize every part of the duck to the fullest extent and maximize the potential of the duck, after harvesting ducks, I prefer to do a full break down. The breasts on a duck are best cooked quickly to medium-rare whereas the legs are best slow cooked until they’re well done and falling off the bone. So separating out the breasts and the legs gives you the best chance to optimize each piece of meat. When you separate the legs and breasts, you then get to save the breast bone, back bone, neck, head, and feet for stock. The legs and breasts have excess fat that isn’t necessary for cooking or serving, so it can be trimmed off and rendered.

After breaking down the duck I prefer to vacuum seal and freeze breasts and legs in packages that are sized appropriately for a single meal for my family. On the largest ducks, the wings can be saved and used much like the legs, but on most ducks the wings are small and are best suited for stock. Remove the tongues from the head and save them until you have at least 30-40 accumulated. Heads, feet, necks , back bones, and breast bones all go to the stockpot. The heads and feet might be alarming to see in a stockpot, but there is a significant amount of gelatin to be extracted from the feet and heads.

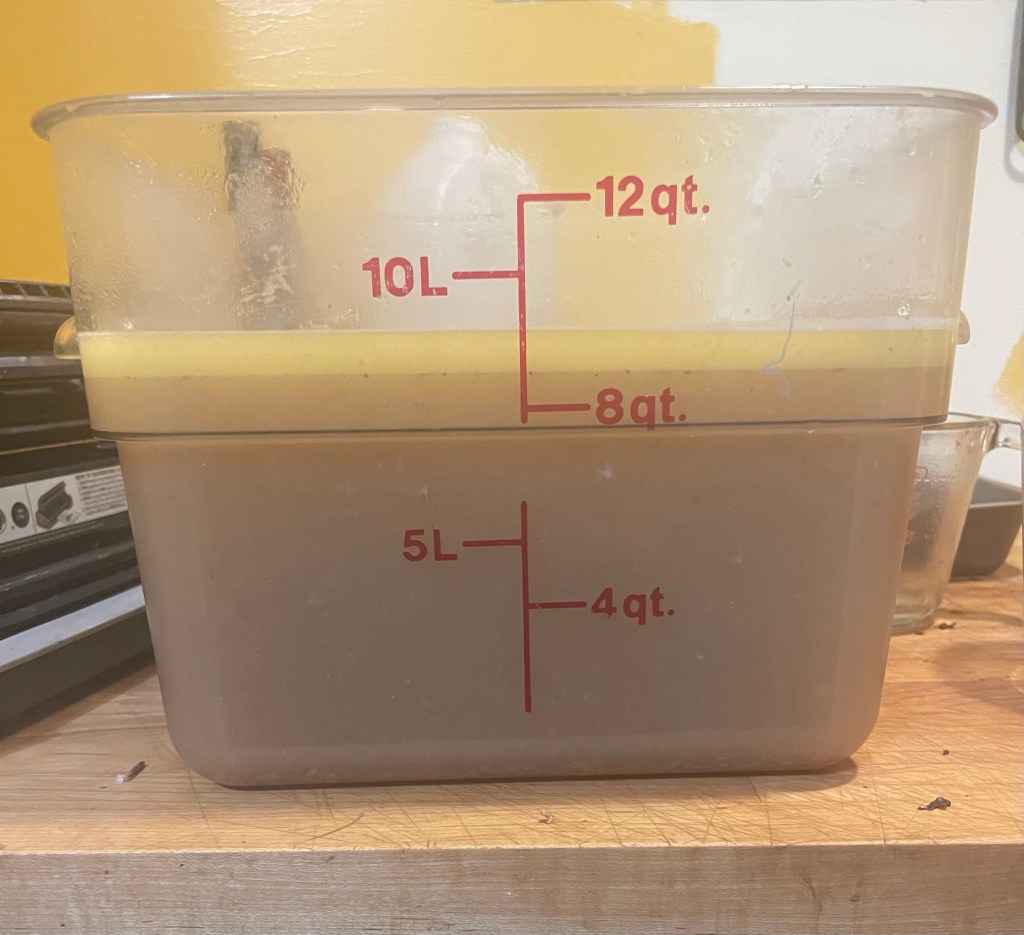

Homemade stock from any animal is almost always more gelatinous and tastier than store bought stock. Duck stock in particular though is extremely rich and creamy. To make stock, simply cover all of the parts meaty and boney bits with water and simmer for a minimum of 8 hours. I prefer to keep the stock simple without any herbs or vegetables so that I can keep my options open when I use it later on. You can always season or doctor up the stock to suit an individual dish if you leave it basic. Leaving out the herbs and vegetables, you really can’t overcook the stock. I normally start simmering stock at night, strain it when I wake up in the morning, put it in the refrigerator before heading to work, and then when I get home the fat has separated to the top and it is ready to skim. The stock should be gelatinous when cold. You can freeze stock for months at a time or refrigerate it for about a week. I prefer to pressure can it to save freezer space. To can, process pint jars for 20 minutes at 15 psi or quarts for 25 minutes at 15 psi with 1″ of headspace. Do not attempt to can stock or any meat products with a bath canner, always do pressure canning and follow USDA canning guidelines to ensure food safety. Fat free stock will keep longer than stock that doesn’t have the fat removed.

Rendering duck fat is equally simple. Any excess skin that you trimmed off the duck can be covered with water and simmered. The fat will begin to render and the liquid will turn cloudy. After 30-45 minutes, the liquid will turn yellow and transparent. Check the temperature and if it’s above the temperature that water boils at your elevation, it is pure fat. Strain the fat through a fine mesh strainer and refrigerate. Fat lasts up to a year in an airtight container if it’s pure and refrigerated.

Leave a comment